The Hampline is one of ioby’s favorite campaigns for a lot of reasons. It’s not only because the Hampline was ioby’s first campaign in Memphis, ioby’s first campaign to raise funds for hard infrastructure, and ioby’s highest grossing campaign to date. The project is to us a brilliant collaboration, blending commercial revitalization, placemaking, cycling infrastructure and the arts in a community suffering from disinvestment. It’s an important and rich story, and we’re proud to play a role in the success of the project.

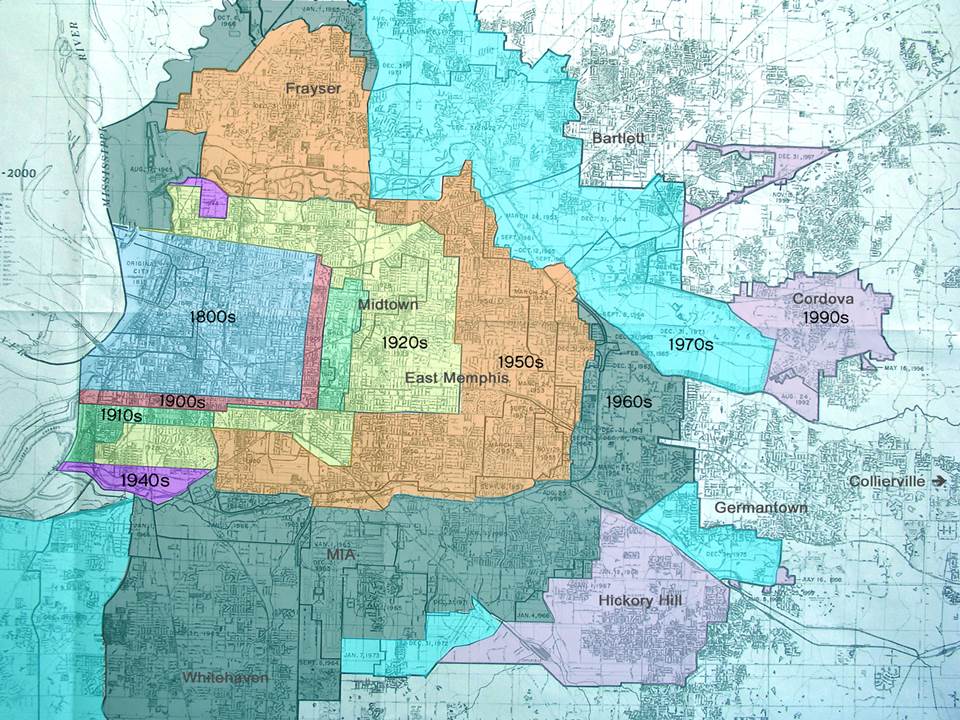

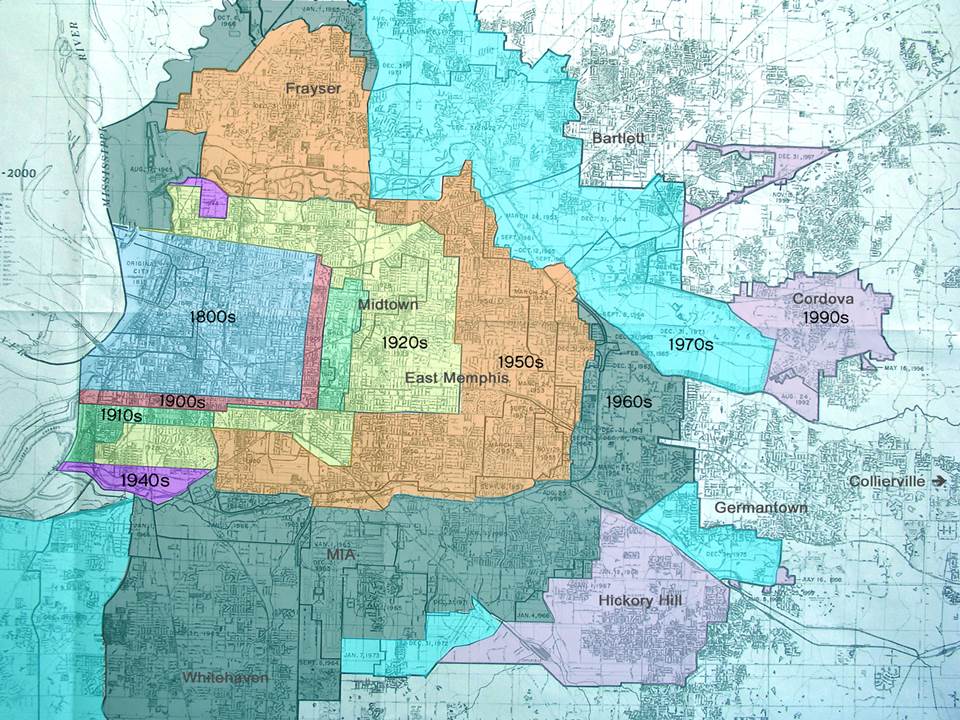

Like many U.S. cities, Memphis, Tennessee has suffered from residents moving out from the urban core to the suburbs. Between 1970 and 2010, the city population grew by 4% while the geographic area grew by 55%. The city limits doubled in size, but population remained flat, and residents packed up and moved to the outer edges of the city. Dispersion created lower density, leaving the core looking like Swiss cheese, with more than 50,000 vacant lots in the city.

Population shifts were coupled with the construction of I-40. Although Memphis is home to the notorious Supreme Court case Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe (1971) that stopped the construction of 1-40 through an established neighborhood and central park, not all neighborhoods fared so well. Similar to the way that the Cross Bronx Expressway cut off the South Bronx from the rest of NYC and compounded socio-economic barriers with a lack of physical geographic access, I-40 cut right through Binghampton, putting five lanes of high-speed traffic between the residential area and the established commercial district on Broad Avenue.

Binghampton, lovingly nicknamed “The Hamp,” is today a neighborhood of about two square miles and 9,000 residents. The median income is $26,000, and nearly 50% of residents have average household incomes below $20,000. Of the residents, 35% live below the poverty level. In recent years, the neighborhood has suffered from 30% population decline, with a 10-14% vacancy for homes in the area.

It’s not surprising that this is the case. It’s not easy to live in the Hamp. There are two active rail lines and an expressway with dangerous cross traffic. Vacant properties have led to an increase in blight.

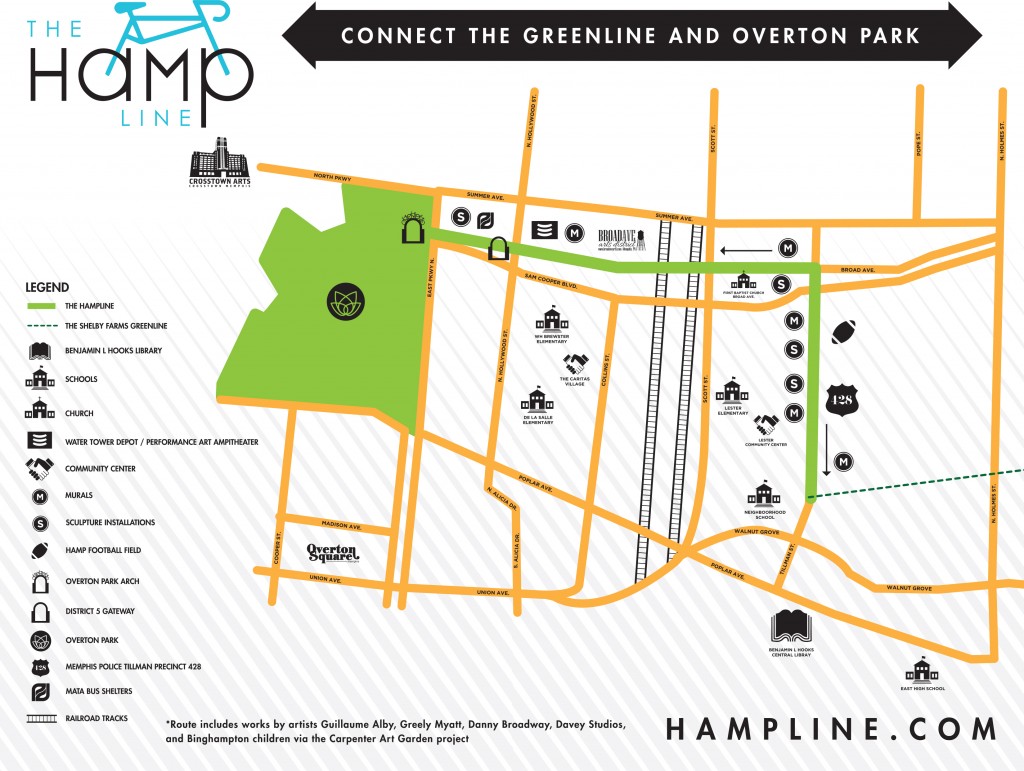

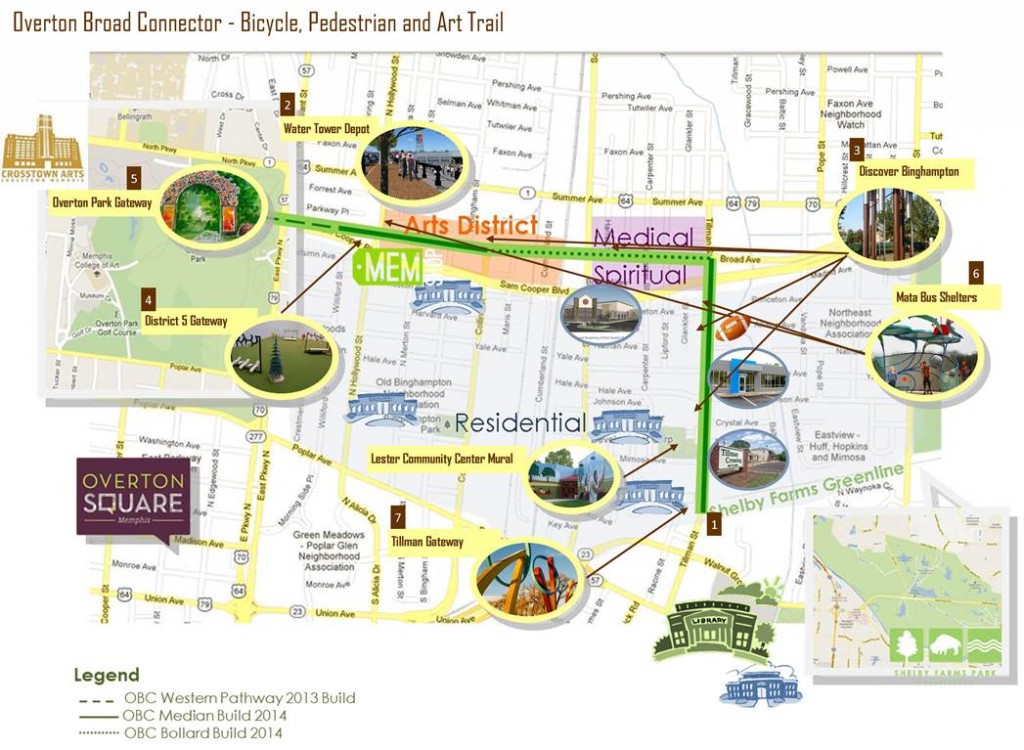

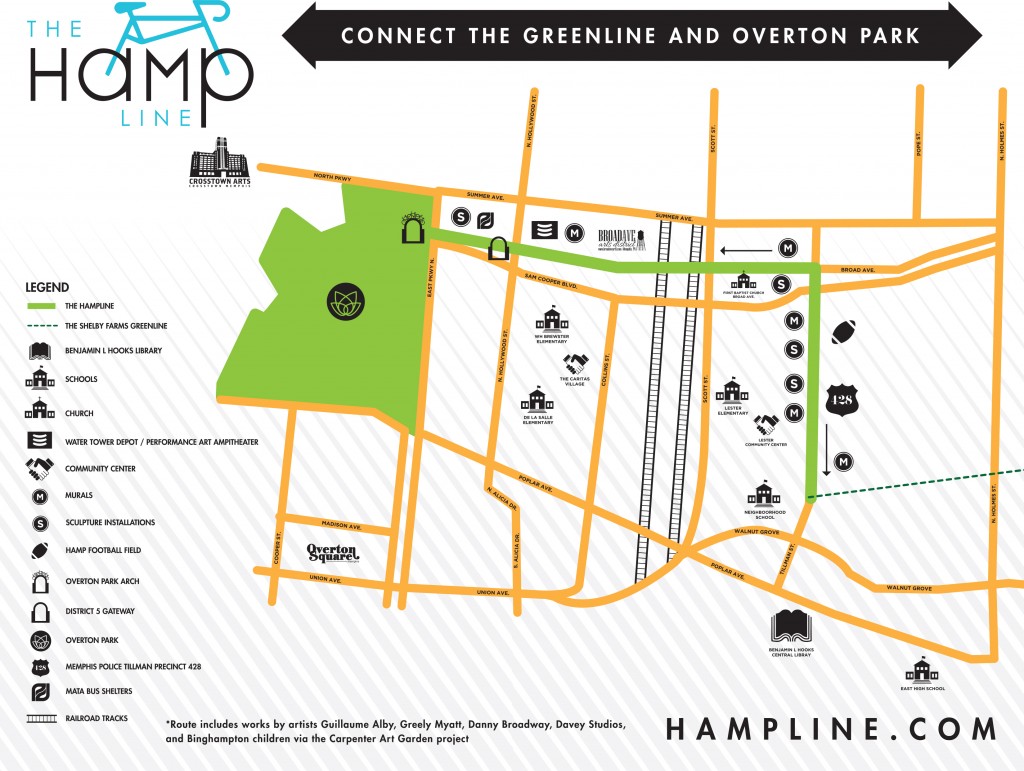

But the neighborhood is literally surrounded by assets. To the west are the famous Overton Park, Rhodes College, the Vollintine-Evergreen Greenline, Downtown Memphis and its historic Beale Street, and the beautiful Mississippi River. To the east are Shelby Farms Park, the Greenline Extension, the Wolf River Greenway, and thriving neighborhoods. The opportunity was that connecting these assets, through Binghampton, and several other neighborhoods, would strengthen Memphis’ urban core.

In 2006, the city of Memphis began a charrette process using Broad Avenue as a test case, and the planning galvanized the neighborhood and created a business association. Together, residents and business owners came to believe that Broad Avenue could be a place for economic vitality.

In 2008, there was just one lonely mile of bike lane in Memphis, and the paths to the 4,500-acre Shelby Farms Park were unsuitable for biking, giving Memphis the unenviable position of “Worst City for Biking” (as ranked by Bicycling Magazine—along with another ioby priority city, Miami—in 2008 and 2010). Inspired by advocates, Mayor A C Wharton set about changing that, by hiring the city’s first bike-ped coordinator and setting a goal of adding 55 miles of bike facilities within city limits. Soon to follow was the Shelby Farms Greenline, a 6.5 mile bike lane connecting Midtown Memphis, just on the other side of Overton Park, to Shelby Farms.

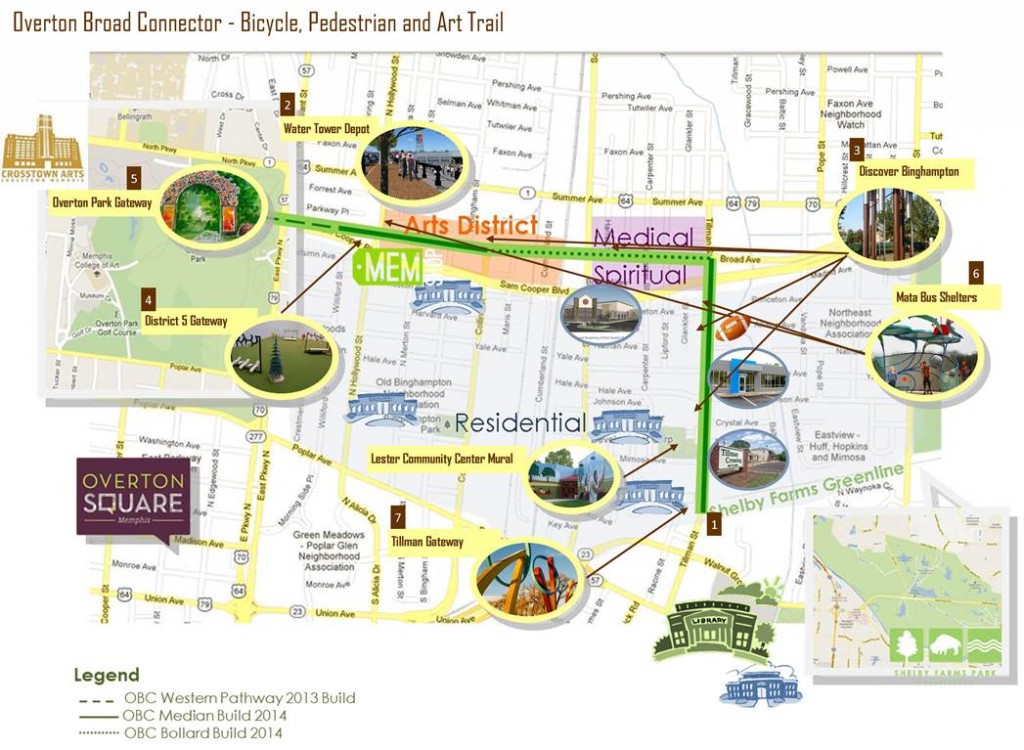

Livable Memphis, a program of the Community Development Council of Greater Memphis, saw an opportunity to connect these two great assets—grounding a major cycling highway while bringing traffic through an emerging business and arts district. As with many neighborhoods of disinvestment and blight, Binghampton had a reputation for crime to overcome. Although Binghampton’s “actual” crime rate was decreasing, nascent revitalization efforts and connecting assets would further reduce Binghampton’s “perceived” crime.

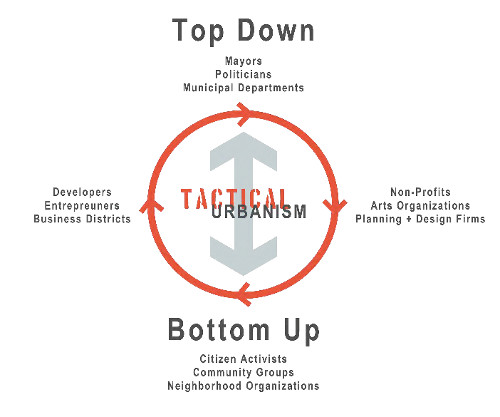

To jumpstart the pre-vitalization process and overcome perceptions, the Livable Memphis, the Broad Avenue Arts District, and the Binghampton Development Corporation, and the owner of an anchor business, T Clifton Arts, drew on a tactical urbanism tool from Dallas, Texas, called Build a Better Block.

The Better Block method, developed by Jason Roberts, uses a 24-hour intervention to reimagine small public spaces in commercial corridors, as if the corridor were thriving, as it perhaps was in the past. Pop-up businesses, public arts, and temporary installations allow residents to reimagine the use of public space, without the investment and the time to make permanent capital improvements.

For Binghampton, the Better Block method was translated for the locality, and A New Face for An Old Broad was born. For a single weekend, the desolate Broad Avenue was transformed into a thriving commercial district, with protected bike lanes and cultural programming. Watch the videos about New Face for an Old Broad here.

And this was just the beginning. What followed over the next year was $2.5 million in private investment, and in the next 3 years, more than $18 million. By the fourth year, the commercial district had 95% occupancy. As investments in local business boomed, cycling advocates began fundraising for the infrastructure to build the two-mile connection between Overton Park and the Shelby Farms Greenline, at that time called the Overton-Broad connector.

The $4.5 million bike lane would be the first of its kind in the United States. A two-way, protected, signalized cycle track would run straight through the emerging commercial district. Neighborhood and cycling advocates, businesses and the City raised federal, state, city and private funds, but in August of 2013, was faced with a $70,000 gap.

They could wait for the next city council cycle to request the remaining funds and delay the project, or compromise the safe and innovative design for the route. Or, they could raise the funds themselves from their friends, neighbors, and folks who would like to use the route.

The groups leading the charge – the Broad Avenue Arts District, Livable Memphis and T. Clifton Arts – and their leaders – Pat Brown, Sarah Newstok and Sara Studdard — approached ioby with their challenge to raise $70,000 by Thanksgiving. Raising the remaining funds would mean groundbreaking would begin in April and the construction would be completed in phases through Spring 2015.

The leaders agreed that their catchy fundraising campaign needed a title that would be easy to remember and authentic to the Hamp neighborhood’s unique character. After some deliberation, the Hampline was born.

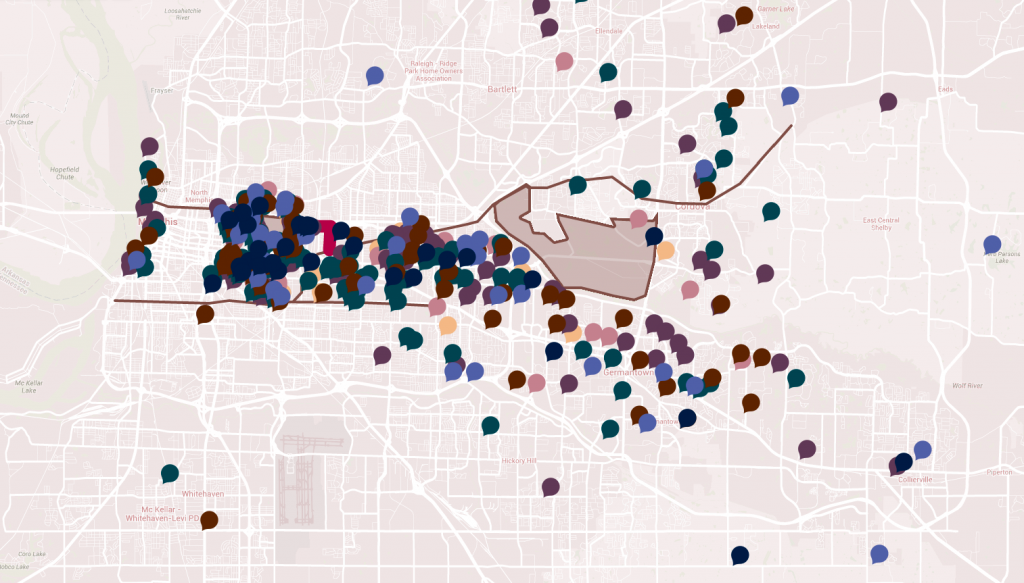

The Hampline team started their campaign by asking their closest networks – friends, family, and colleagues – to donate $50 each. At the same time, a local bicycle club called the Memphis Hightailers came to the table with $2,500 in matching funds for donations made by their members. The team prudently decided to cap the amount of match funds applied to each donation at $50, so that donors with large contributions would not drain the pot too quickly. Using this match fund as an incentive, the team raised $2,530 in citizen philanthropy within the first four days of launching. By the end of the first week of the campaign, the team had raised close to $8,000 and the press was starting to pick up on this exciting new effort. They repeated this successful strategy with the Evergreen Neighborhood Association.

Recognizing that a $70,000 goal seemed daunting and unattainable for many donors who were only capable of making small contributions, Pat, Sarah, and Sara wisely began to make asks in bite-sized chunks. Rather than focus on the lofty total that they needed to raise, they began to ask many of their donors for $55, which they calculated to be enough to sponsor exactly one foot of the Hampline.

About two weeks into the campaign, with about half of the money raised, the Hampline’s tremendous progress started to plateau. The team worked with ioby’s team of strategists to reorient and reenergize their campaign. They assigned fundraising roles and responsibilities to the campaign’s most ardent supporters, added some new prospects to their list, and identified new opportunities to make in-person asks.

Working in tandem, the team made a series of phone calls, sent out emails, and appeared at community gatherings to share their work, make asks, and recruit new supporters. The Hampline also benefited from two additional matches over the course of the campaign, thanks to generous support from Alta Planning and Design and the Hyde Family Foundations. Ultimately, the combination of matching funds and the team’s direct and explicit style of making asks were enough to get the team across the finish line on time.

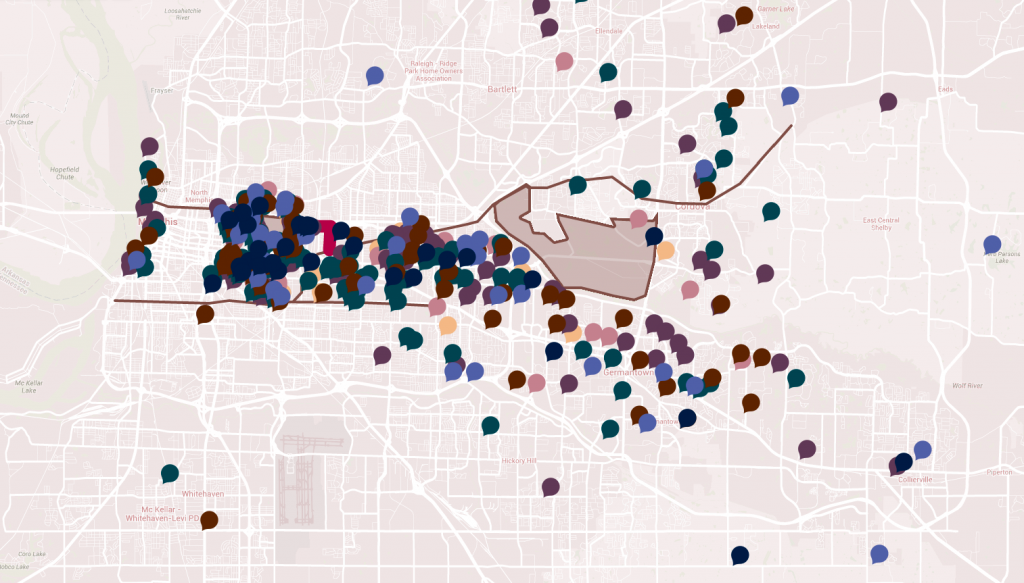

The result was that more than 700 people, living with just a couple miles of the future bike lane gave to the campaign, the median donation was $50, but many people giving just $9.01 (the city’s area code). Not only did the local giving demonstrate a groundswell of community support, but it also fostered a culture of ownership and local stewardship of the space.

Donating to the Hampline became the cause célèbre of the city. Groundbreaking took place as planned in April, and the archway went up. Today, Broad Avenue has more than 95% occupancy. Additional private funding has supported cultural amenities in the area, creative bus stops and an archway made of bicycles at the entrance of Overton Park. The ArtPlace America grant has enlivened the avenue to zumba, dancing and performance arts on weekends. All of this transforming the neighborhood nearly unrecognizable to its former self just five years ago.